No products in the cart.

Entering into a treaty with other groups for reasons of trade, gaining a living off the land, or establishing alliances for protection has been done by peoples all over the world since the beginning of time. And so it was with Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Indigenous peoples in the area now called Manitoba entered into such arrangements with one another, before the settling of Canada by Europeans. The treaty-making process with the Europeans was initially set down in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. There, the British crown issued instructions on how settlers were to go out and start living on the land. Only the British crown could enter into land arrangements with Indigenous nations. Settlers could then obtain land possession from the colonial authorities.

The first treaty in Manitoba was the Peguis – Selkirk Treaty of 1817 under whose terms Lord Selkirk entered into a relationship on land and annual payments with Chief Peguis and his people on the Red River to strengthen the legitimacy of his nascent colony which was facing questions about land rights by Indigenous peoples in the area.

As has occurred in other places on our planet, problems in interpretation of treaties such as the Selkirk Treaty arose soon after they were signed. The Hudson Bay said the lands referred to were ceded and surrendered to them as the rightful owner of all the entire region – never having itself entered into any arrangement with Indigenous peoples for land use. Indigenous peoples, not being familiar with the concept of human beings “owning” tracts of land, have always thought the claim absurd. What they were familiar with was sharing the land with others to enable mutual benefit and this is how they continue to interpret their treaty arrangements today.

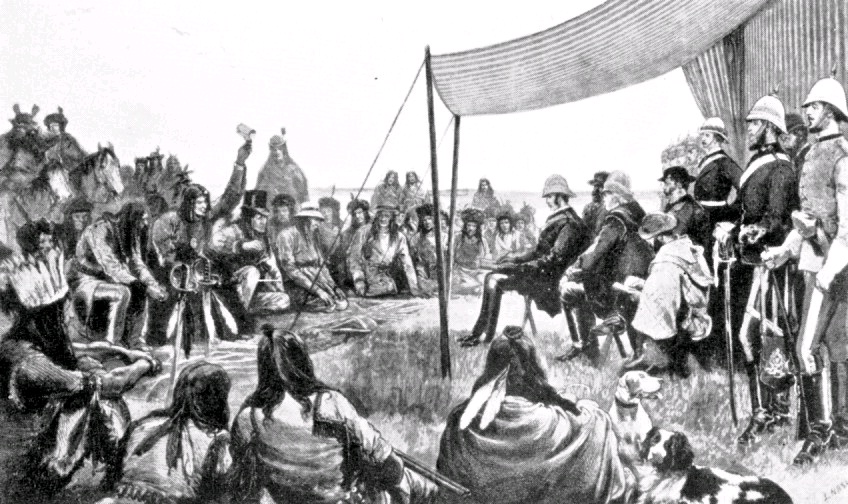

In the 1870’s the Canadian government moved to “open up” the west for expansion and settlement. Extending the railroad to link up the province of British Columbia was crucial to that province agreeing to be a part of Canada. The government negotiators had orders to get signatures on the treaty documents by whatever means necessary. The Indigenous signatories knew change was coming and sought to negotiate terms that would allow them a means to have a livelihood in the new order. They had the Selkirk Treaty experience in their heads and settled on the concept of sharing the land and continuing a relationship for mutual benefit. The government negotiators understood the arrangement as a cession and surrender.

Canada continues to adhere to the position that the land was ceded and surrendered. Canada’s website sums up its treaty position as follows: “The historic treaties signed after 1763 provided large areas of land, occupied by First Nations, to the Crown (transferring their Aboriginal title to the Crown) in exchange for reserve lands and other benefits.”

There is hope for reconciliation and agreement on what exactly the treaties mean among the parties, perhaps to be rekindled in a revised statement in the future. In 2006, independent but “neutral “ treaty commissions were set up in Manitoba and Saskatchewan to “conduct a number of activities in relation to historic treaties. This includes public education, research and facilitating discussions on treaty issues.” The terms of reference of the Manitoba Treaty Relations commission web site states: “Recognition that the Treaty relationship is dynamic and will evolve over time.”